John Kipling was Rudyard’s only son, not quite his “best beloved” as that position was always held by his daughter Josephine who had died of pneumonia in 1899 when she was only 6. In fact, John emerges from his father’s biographies as someone who had “not turned out altogether well” (Martin Seymour-Smith), was backward in his school work (Charles Carrington) and caused his father anxiety (Lord Birkenhead). Certainly the letters Kipling sent to John at school are full of pleas for him to work harder, steer clear of ‘beastliness’, lose gracefully, and not be so carping and critical. There is a gap in the letters from October 1913 to September 1914, a crucial period in John’s life when he was removed from school, Wellington, and sent to an army crammers. When war broke out in August John was still only 16. Nevertheless he wanted to join up and made several unsuccessful attempts to do so but was always refused on the grounds of short sightedness. Eventually his father pulled strings and John received a commission in the Irish Guards.

Without any knowledge of what passed between father and son, there is a suspicion that John might not have been quite so keen on being in the army as his father was. Rudyard may not have greeted the war with the same enthusiasm as Rupert Brooke but his first poem, with the Hun at the gate, was a stern reminder that:

There is but one task for all –

One life for each to give.

Who stands if freedom fall?

Who dies if England live?

However, to some there’s been a suspicion that the one life Rudyard was prepared to give was his son’s rather than his own.

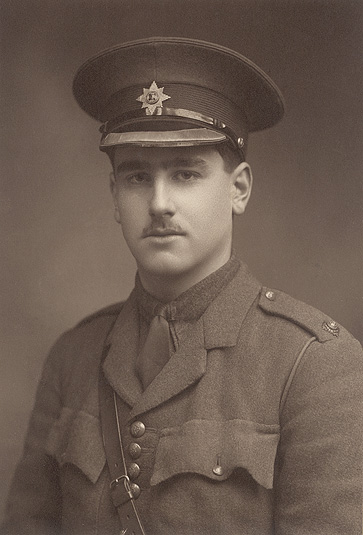

It’s something of a surprise therefore to come across a photograph of a mature, prepossessing young man in uniform and to realise that this is John. And to see from the letters that far from being a disappointment to his father, Rudyard is undisguisedly proud of his officer son, proud that John is a volunteer, that he is so young, and that he is coping so well. One can sense Rudyard’s keen pleasure when, following John’s first home visit, he described to his daughter Elsie how, “We talked and we talked and we talked – this grown up man of the world and I.” But the pleasure was tinged with fear. Rider Haggard, a good friend of the Kiplings, saw them on 24 March 1915 and recorded in his diary that neither of them had looked well.

“Their boy John is an officer in the Irish Guards and you can see they are terrified lest he should be sent to the front and killed.”

It is only once John is in the army that any letters from him appear in the Kipling Archive at the University of Sussex. This is the first time we hear his own voice and it immediately dispels any fears that he might have been an unwilling victim of his father’s military enthusiasm. Although John’s handwriting is immature and his spelling uncertain, he comes across as confident, energetic and full of initiative, an opinion which the army must have shared to judge by the responsibility it gave him.

John loved the army. It was his chosen profession but without the war he might never have got a commission because of his poor sight. The letters also reveal a real closeness between father and son. They are full of the sort of trivia that are only of interest to people who are in real contact: reports of trivial happenings, small bets, private jokes. The truth about Rudyard’s relationship with John is probably best summarised in a letter father wrote to son in which with typical British understatement but evident fondness he says,

I wish I didn’t miss you so much as I do , old man. You were a huge nuisance at times but I seem to have got fond of you in some incomprehensible way.

On Monday 16 August, one day short of his eighteenth birthday, and with his parents signed permission to allow him to serve overseas, John embarked for France. He is delighted to be there at last and declares at the end of his first letter home – “This is the life”. A month later, definitely aware of his own mortality, he writes: “if I live to get back again I’m going to get myself the smartest two seater Hispano-Suiza that can be got and get a bit of enjoyment of life out of it”. Although at that very moment his idea of luxury would have been a hot tap. The letter finishes on a more ominous note:

“By the way, the next time you are in town would you get me an identification disc as I have gone and lost mine. I think you could get one at the stores. Just an aluminium disc, with a string through it like this. (Draws image of disc with a single small hole and the words ‘2nd Lt J. Kipling Irish Guards’) About this size. It is quite impossible to get one out here or I wouldn’t trouble you about it. It is a routine order that we have to have them.”

The countdown to battle had begun and John knew it. In a letter home on 10 September he had written, “Dad most likely knows what is going to happen out here in ten days’.

Believing that this offensive was at last going to result in a break through and end the war, the Irish Guards went into action on 27 September. John went missing that same day. It was his first engagement. The news reached Bateman’s, the Kipling’s home in Sussex, on 2 October. One source says that it was brought by Andrew Bonar-Law, Conservative Colonial Secretary in Asquith’s Coalition Government. Kipling met him with the words, “You have come to tell me my son is dead”.

The Kiplings rigidly suppressed their grief and closed themselves off from the outside world. But they were only too aware that they were no different from any other bereaved family.As Rudyard wrote to his old school friend, General Lionel Dunsterville:

It was a short life. I’m sorry that all the years work ended in that one afternoon but – lots of people are in our position – and it’s something to have bred a man. The wife is standing it wonderfully tho’ she, of course, clings to the bare hope of his being a prisoner. I’ve seen what shells can do, and I don’t.”

But it would be a mistake to think they didn’t care. Howell Gwynne, editor of the Morning Post went to visit Kipling a few days after the news arrived and wrote:

When I arrived, he said ‘What have you come down for?’ I said ‘To see what I can do’. ‘You can do nothing’ he said but I saw a quiver in his lips which showed how the thing had gone home.

And when someone offered them a bull dog puppy, hoping it would bring them comfort, they thought about it and refused, the memories it conjured were too painful.

“When all the world was young … John without shoes or stockings, owned and was owned by one ‘Jumbo’ a brindle and white bulldog who chaperoned him on walks, played with him and being forbidden to sleep with him devoutly slept outside his door. All those good years … are mixed up with the memories of a small boy and a large bull dog and we didn’t realise how horribly alive they were until we talked over your letter.”

Letters of condolence arrived from all over the world. A few of them remain in the Kipling Archive at Sussex. Words of comfort took a different form in those days, I’m not sure we’d appreciate them today, I’m not sure the Kiplings appreciated them then: “I do not imagine that any two parents in England will more cheerfully make the sacrifice or more heroically bear the loss,” (Lord Curzon); “There are so many things worse than death” (Theodore Roosevelt). The novelist Marie Corelli struck the right note when she wrote, “You forsaw what was coming years ago – but few listened to your clarion call of warning”. To her the soldiers were the innocent and their fathers the guilty ones, guilty because they had ignored the warnings about German militarism. This is exactly how Kipling felt, and it is the meaning behind his famous epitaph:

If any question why we died,

Tell them, because our fathers lied.

The desire to know what happened to John obsessed the Kiplings. By 12 November they had discovered that he had led his platoon over a mile of open country towards a small wood. His Company Commander, Captain Bird, told them:

The wood was captured but it was under heavy fire of every variety. Two of my men say they saw your son limping, just by the Red House, and one said he said he saw him fall, somebody ran to his assistance, probably his orderly who is also missing. The Platoon Sergeant of No. 5 however tells me your son did not go to the Red House … I am very hopeful that he is a prisoner. “

Kipling met Rider Haggard in London on 22 December. Haunted by his friends’ sorrow, Haggard made every effort to find out what he could. Eventually he discovered a guardsman, Bowe, who visited Haggard and related how he had seen John Kipling blown to pieces by a shell. Haggard felt pleased to be able to send his friend a signed statement from Bowe to this effect. But later the soldier who had accompanied Bowe wrote to Haggard to say that Bowe had not told the truth. What Bowe had told this soldier was that he had seen Mr Kipling heading back to the rear, trying to fasten a field dressing round his mouth, which had been badly shattered by a piece of shell. Bowe would have helped him but the officer was crying and Bowe didn’t want to humiliate him. Haggard did not pass this information on to the Kiplings.

Many of the bereaved took solace in Spiritualism and Carrie, Rudyard’s wife, was tempted to try this for herself since she was desperate to make contact with John. But Spiritualism was something that Rudyard vehemently spurned despite, or maybe because, of his sister Trixie’s belief in it. Yet when Rudyard was asked if he thought there was anything in Spiritualism he said he knew for certain that there was. It was the money the mediums made from the gullible bereaved that most offended him, together with the revolting way they conveyed their communications with the dead – twitching, stiffening, slavering and groaning. But Kipling understood what drove the bereaved and perhaps there is some truth in the newspaper stories that the Kiplings did consult mediums, not so they could make contact with John but so that they could locate his body. They never did.

Kipling sought consolation in his work. In 1917 he was commissioned to write the ‘History of the Irish Guards in the Great War’. It was the research that Kipling did for this history that must have finally convinced him that his son was dead. In the course of it he interviewed hundreds of guardsmen and none of them had any news of John, nor was he discovered lurking in some hospital bed suffering from loss of memory. When the History reached the 27 September 1915 Kipling was able to cover the event with impeccable detachment reporting that:

Of the officers, 2nd Lieutenant Pakenham Law had died of wounds; 2nd Lieutenants Clifford and Kipling were missing …It was a fair average for the day of a debut, and taught them something for their future guidance.

At this point many commentators have expostulated at Kipling’s callous indifference. What they don’t do is quote the following sentences.

Their Commanding Officer told them so at Adjutant’s Parade … but it does not seem to have occurred to any one to suggest that direct Infantry attacks, after ninety-minute bombardments, on work begotten out of a generation of thought and prevision, scientifically built up by immense labour and applied science, and developed against all contingencies through nine months, are not likely to find a fortunate issue.

In 1917 Kipling was appointed to the Imperial War Graves Commission as its literary advisor. Every word the Commission used was written, chosen or approved by him, including the dignified inscription on the headstone of the unidentified dead, ‘A soldier of the Great War. Known unto God’. This could be adapted to incorporate any scrap of information that could be discovered about the dead man: a Canadian soldier, a German soldier, a Corporal of the Black Watch, a Lieutenant in the Irish Guards.

The Kiplings chose Charles Wheeler (1892-1974) to design a memorial for John for St Batholomew’s Church, Burwash in Sussex. It’s a circular bronze plaque with the badge of the Irish Guards inside a wreath of laurels together with the words:

To the memory

of

John Kipling

Lieutenant Second Battalion

Irish Guards the only son of

Rudyard and Caroline Kipling

of Bateman’s who fell at

THE BATTLE OF LOOS

The 27th September 1915

aged

Eighteen years and six weeks

‘Qui ante diem

periit’

Kipling, who had done his work for the War Graves Commission so well, and who had expressed the grief of the whole nation with great dignity and without rancour or bitterness or triumphalism, could not be quite so dispassionate for his own son. Note John’s age, 18 years and 6 weeks. The precision is a covert criticism of all those, namely the Liberals and Socialists, whose complacency in the face of German militarism had left Britain ill prepared for war in 1914. And who, even after war was declared, dragged their heels over conscription so that in the early years the army had to depend on volunteers and some of them, like John, were only boys. And in another departure from his Commission work, Kipling, who had spoken so plainly for the nation, quoted in Latin for his son. ‘Qui ante diem periit’, who died before his time. The quote comes from Henry Newbolt’s poem, Clifton Chapel. A father, introducing his son to his old school chapel, points out the plaques on the wall of old boys who have been killed in the service of their country.

God send you fortune: yet be sure,

Among the lights that gleam and pass,

You’ll live to follow none more pure

Than that which glows on yonder brass:

‘Qui procul hinc,’ the legend’s writ, –

The frontier grave is far away –

‘Qui ante diem periit:

Sed miles, sed pro patria.’

He died far away, and before his time, but as a soldier and for his country. This is exactly what John did.

There is a postscript to the story. In 1919 a body was brought in from the old Loos battlefield. Unrecognisable and with no identification disc, all that could be told about him was that he had been a lieutenant in the Irish Guards. The body was buried in St Mary’s Advanced Dressing Station Cemetery under a headstone which read, ‘A Lieutenant of the Irish Guards. Known unto God.’ In 1991, research by a War Graves Commission officer concluded that on balance this lieutenant had to be John Kipling. Consequently the Commission altered the headstone to reflect the new identity. The identification has been fiercely challenged by authors Tonie and Valmai Holt in their book My Boy Jack. In the face of this challenge perhaps the best inscription remains, ‘Known unto God’.

Evening,

Thank you for the informative article. Wolverhampton has strong links with Rudyard Kipling as his mother lived in Wolverhampton for sometime whilst her father was the preacher at the Darlington Methodist church. WCHS has a blue plaque for her and her sisters. In addition to this the sculptor Sir Charles Wheeler (born in Wolvhampton) designed and made the memorial for John Kipling at Burwash and not Herbert Baker http://www.iwm.org.uk/memorials/item/memorial/58393

best regards

Wolverhampton Civic and Historical Society

Thank you for your comments and for your information that it was Sir Charles Wheeler who designed and made John Kipling’s memorial for Burwash Church. I’m pretty sure I got my information about Baker designing the memorial from the DAC Sussex; it was on the application form – of course I can’t find the reference now! Baker was one of Wheeler’s early career patrons so maybe there was some connection between the two over the memorial. Nevertheless I shall change the reference in my article and am grateful to you for pointing it out. Thank you!