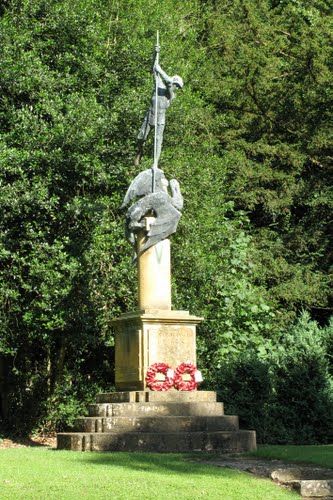

At an isolated crossroads on the busy Stow-on-the-Wold, Tewkesbury Road, there’s an elegant bronze statue of St George piercing the dragon’s breast with his slender lance. Carved on the base are the words:

“Men of Stanway

For a tomb they have an altar

For lamentation memory

And for pity praise”

Among the eleven names carved on this the Stanway war memorial are those of Hugo Francis Charteris, Lord Elcho, and Yvo Alan Charteris, the eldest and the youngest sons of the Earl and Countess of Wemyss of Stanway House.

It was typical of Mary Wemyss that she should commemorate her sons on the village memorial in this way, rather than on an expensive memorial of their own, for her family were part of the village and the village were part of her family. Yet Stanway House was also close to the heart of Westminster due in no small part to Mary’s long-standing close friendship with Arthur Balfour. A one-time leader of the Conservative Party, Balfour had been prime minister from 1902 to 1906. The Westminster connection was emphasised when Mary’s daughter, Cynthia Charteris, married Herbert Asquith, younger son of the Liberal prime minister Herbert Henry Asquith.

Stanway House was a favourite meeting place for The Souls, an aristocratic group of friends

whose interests were more cerebral and artistic than the Prince of Wales’ Marlborough House set. Not that Stanway House was smart or richly appointed or even very comfortable; its appeal lay in the beauty of its ancient Tudor buildings and in the delightful ambience created by Mary Wemyss, a thoughtful and sympathetic hostess. She had been born Mary Wyndham, one of three sisters immortalised in John Singer Sargent’s portrait, the Three Graces.

Mary married Hugo Charteris, then Lord Elcho, in 1883. Hugo was born in 1884 and by 1914 was married to Letty Manners, daughter of the Duke of Rutland. Yvo was born in 1896 and in 1914 was still at school.

It was from school, Eton, where he was a King’s Scholar, that Yvo wrote home that autumn in high spirits :

I am thinking of making money by writing letters from the Front and sending them to the Daily Mirror, with plenty of dashes, passages deleted by censors, metaphors from the football field and improbable but stirring incidents.

However, by Christmas, having secured a place at Balliol, he was no longer content to remain on the sidelines, saying that he found school increasingly irrelevant and telling his parents that anyone over seventeen “with any gumption” had already left to join the army. Eventually the Wemyss relented and Yvo left school mid-term in February 1915.

He was commissioned into the King’s Royal Rifle Corps and a few weeks later, on 15 March, was confirmed in Winchcombe Church. The event impressed itself on his mother’s memory: “Yvo’s fair face and slender figure, kneeling, khaki-clad, made a never-to-be-forgotten picture of consecrated youth”.

Was this image the origin of a small bronze roundel that used to hang in the porch of Stanway Church, the same image that forms the centrepiece of the memorial to Madeline Wyndham’s five grandsons – Hugo Charter, Yvo Charteris, Percy Lyulph Wyndham, George Hereman Wyndham, Edward Wyndham Tennant – in the church in East Knoyle?

St Mary’s East Knoyle, memorial to the five grandsons of Madeline Wyndham who were killed in the Great War

The next day Yvo joined his regiment in training on the Isle of Sheppey – and acquired a motorbike. With typical humour, he described to his sister Mary how,

“A monster bicycle has arrived from Bim [his cousin Edward Wyndham Tennant], 6 h.p. and only one gear; with commendable courage, never having sat a machine before, I rode it from the station, the only difficulty is that it won’t go slow. Yesterday I ran amok and knocked down a rifleman, however saluting from the dust he apologised profusely, thus showing the glorious spirit of discipline that pervades the British army and will eventually bring the Kaiser to the doom he deserves.”

Osbert Sitwell was one of Yvo’s friends and in his book, Laughter in the Next Room, Sitwell provides us with a welcome description of Yvo who otherwise only comes to us via his family and to them he was always the baby. To Sitwell, Yvo was one of those people whose “breeding showed in his whole appearance” and who was,

without any degree of precocity, detached and ironic, nonchalant, in spite of decided opinions, and manifested in everything about him, even in the way he wore his top-hat, innate style.

In April, after considerable heart searching, Yvo transferred to the Grenadier Guards. He hated the Isle of Sheppey and the Grenadier Guards trained in London, which was much more to his liking as he could spend more time at home. On 5 September 1915, the regiment received notification that they were about to be sent overseas. His mother remembered the moment precisely and recorded it in her diary:

I returned about seven and Yvo, in his red dressing gown, opened the front door. He had a scrap of paper in his hand on which was typed his warning to go to Flanders in the near future.

She described the scene to her mother, Madeline Wyndham, who months later gave Mary a silver triptych containing an enamel portrait of Yvo wearing a flame-coloured robe. It was the work of Alexander Fisher who later made the Stanway war memorial.

Yvo had a week’s embarkation leave. He and his mother made a rapid trip up to Gosford in East Lothian, the Wemyss’ Scottish seat, to say good-bye to the family. On the sleeper coming home Mary watched over him whilst he slept, desperately trying to hang on to the moment and not think about the future.

He looked so white and still, and though I said to myself, he is still safe, he is still alive and under my wing, yet all the time as I watched him sleeping peacefully, there lurked beneath the shallow safety of the moment a haunting, dreadful fear, and the vision of him lying stretched out cold and dead.

It was impossible not to fear the future; Julian and Billy Grenfell, the sons of one her dearest friends Ettie Desborough, had already both been killed.

The Grenadier Guards arrived in France on 11 September. There were rumours of a big attack and reinforcements were being hurried over. The rumours were true. Two weeks after the Guards’ arrival the Loos offensive was launched. Yvo missed the battle, he had been kept back with the transports, possibly because he was still only eighteen. On 6 October, he celebrated his nineteenth birthday in some captured German trenches eating partridges that had been sent out to him from Scotland.

The next day, the 7th, he wrote to his sister Cynthia reporting that he’d had his first sight of blood at the bottom of a trench and that it had rather disgusted him. On the 13th the British launched a limited attack in an attempt to improve their precarious position on the newly created Loos Salient. On the 17th Yvo was leading a party of bombers in an attempt to capture a German trench when he was caught by enfilading fire from the enemy machine guns and in the words of the official communique “he died instantly”.He had been at the front for precisely five weeks.

Lord Wemyss’ brother worked at the War Office and he got a messenger to ring the Wemyss’ London home where Cynthia, feeling strangely restless and welcoming the diversion, rushed to answer the phone. It never occurred to her that there was anything wrong, even when a strange voice said, “I am speaking from the War Office … we’ve got very bad news here”. She thought they were going to warn her about an impending Zeppelin raid, only when they said, “It’s about Yvo Charteris … you must be prepared for the very worst … ” did she realise what they were about to say.

The family were completely shattered, somehow they had never dreamt that anything could happen to Yvo. According to Cynthia, her father’s reaction was one of naive astonishment, it had just never occurred to him that Yvo could be killed. Cynthia expressed the disbelief of them all when she wrote in her diary,

Oh how it hurts and how little one ever faced the possibility for an instant! Darling, darling little Yvo – the perfect child and youth. How can one not be going to see him again?

Nor was this the only thing she found impossible to believe,

How can one believe it should be the object to kill Yvo? That such a joy dispenser should have been put out of this world on purpose.

Although many of her friends and cousins had already been killed, her own brother’s death was completely different. Whereas for them, she says, she had been able to swallow the ‘high faluting platitudes’ that they were not to be pitied because they were safe and would remain young and glamorous for ever, this would not do for Yvo.

With Yvo I cannot bear it for him. The sheer pity and horror of it is overwhelming, and I am haunted by the feeling that he is disappointed.

But for his mother, Mary Wemyss, it was no more than she had feared from the moment that Yvo had first received his warning. At first she was kept busy arranging a memorial service at Stanway, answering letters and transforming his London bedroom into a shrine where the flame-coloured dressing gown had pride of place. She felt that the room was still full of him and it gave her the comforting feeling that he was going to come back. But as November progressed through to December she began to sleep in Yvo’s bedroom in order to feel close to him, and she complained increasingly of feeling weak and lethargic, and admitting to her diary on Christmas Eve, “I think of Yvo all the time – we all do”. And after her final entry for 1915 she wrote, “I go into a year that Yvo didn’t know, from here and every second I miss him.”

Worse was to befall the family in 1916. Under the entry for Sunday 23 April 1916, Mary recorded a vivid dream. Without the benefit of hindsight she wrote,

I dreamt I saw Ego [Hugo] so distinctly and told Cincie [Cynthia] at breakfast but I forget if it was Saturday or Sunday night. He looked sad and fierce.

Hugo was serving with the Gloucestershire Yeomanry in Egypt where they had been sent in April 1915. In her book, A Family Record,Mary describes her last farewell to her first-born child with heart-breaking control:

“Ego came and lay down beside me; I think we hardly spoke one word. Sadness and strain seemed to vanish, blotted out by a great wave of love, of trust and peace and perfect understanding which left no room for fear or regret. We lived through a few moments of perfect sympathy and the acceptance of destiny, which gives one calm and strength: moments which cannot be described in words, but which are never quite forgotten, and which support one in the days of trial; for love and pride give strength. Ego had never failed me and I could not fail him then. That was my last good-bye.”

Later that night, at midnight, Mary and Hugo’s wife, Letty, went to watch the regiment march out from their barracks at Hunstanton, where they had been guarding the coast:

At first the men were singing, or crooning a wild, rather lovely, murmuring song which mingled with the tramping of the horses and the clinking of their bits. Major Palmer, Tom Stricklnd, Aubrey Wickham Musgrave, and then Ego passed by, and all was silence save the sound of marching; but there was music in the jingle of the harness, and romance in the clank of accoutrements and the thud of the horses’ feet.

When Ego rode by there was a slight pause for a last farewell, and then, looking splendid, he rode away into the darkness.

Last of all came the creaking, groaning transports, and then silence; the place was utterley deserted. The Gallant Glittering Gloucesters had passed out of our sight and we went sadly home. I never saw Ego again.

Two days after Mary’s dream, the family learnt that on 23 April there had been a battle at Katia, east of the Suez Canal. Hugo’s regiment, the Gloucestershire Yeomanry, had been involved and they were informed that he had been slightly wounded in the shoulder. They received no further news and the weeks dragged on into June. The lists of prisoner-of-war came through and his name was not on them not, as did the lists of the wounded and he was not on them either. Nor did anyone in the family receive any kind of communication from Hugo himself. On 30 June Mary confided to her diary,

Hope has never been alive in my heart and she has folded her wings very fast … one must have been very rich to be able to lose so much, two such sons.

The very next day her worst fears were confirmed when a telegram arrived from the French Red Cross – “Lord Elcho fut tue a Katia”. As she admitted to her diary that night,referring to the April dream,

Darling Ego sent me his own message of strong love, and I’m sure he felt ‘Poor mum’ and I got it and never could quite believe that he was alive and the silence told me every day.

On the morning of 23 April a massive Turkish force of over a thousand men attacked the Yeomanry at Katia, hopelessly overwhelming them. Hugo was wounded in the arm but carried on fighting and was seen helping to evacuate the hospital tent when it caught fire. Eventually the Yeomanry’s ammunition ran out and they were forced to surrender. Tom Strickland, married to Hugo’s sister, Mary, was taken prisoner. When he was eventually able to get news out, he told the Wemyss that Hugo had been alive up until the moment that a shell burst over him and that although he, Tom, saw no remains this must have been the moment that he was killed. Hugo’s body was never found and he commemorated on the memorial to the missing in Jerusalem along with 3,076 other men of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force.

Yvo was buried in Sailly-Labourse Communal Cemetery, his men apparently having made a special point of recovering his body. For his headstone inscription the family chose a quotation from A.E. Housman’s A Shropshire Lad XXIII.

“They carry back bright

To the coiner

The mintage of man”

In July 1919 Mary Wemyss went to France. On 10 July she was in Paris. Her diary is empty from 16 July to 4 August but it is difficult to believe that she can have gone to France and not visited Yvo’s grave. In the same poem that Yvo’s inscription comes from, Housman expresses the idea that it would be good to know in advance who it was that was going to die young, a sentiment with which Mary Wemyss cannot have agreed. In her exquisitely written memoir, A Family Record, she states categorically,

It is well for us that we live day by day with our eyes bandaged and do not see what fate has in reserve for us in the future.

Within months of the end of the war Alexander Fisher had been commissioned to design the Stanway war memorial. It was the cause of much anguish and aggravation over the details of the exact design, size, height, position, style of lettering, words of the inscriptions, names that were to be included or excluded, cost and how the money was to be found. It was eventually unveiled on 30 October 1920, All Hallows Eve. The cost was over £600, an enormous sum that was raised from the villages, the Wemyss family, and from their huge circle of friends and associates. Eric Gill carved the names, the decorative details and the inscriptions. The one on the front is from the Greek poet Simonides – For a tomb they have an altar, for lamentation, memory and for pity praise. The inscription on the reverse – For your tomorrow we gave our today – is an extract from an epitaph suggested by J. Maxwell Edmunds and published in Inscriptions Suggested for War Memorials HMSO 1919,

When you go home, tell them of us and say

“For your to-morrows these gave their today.”

This is a brilliant blog, beautifully presented with some real nuggets of fact that have been put together in a way that really helps to today’s reader how our Grandfathers and great grandfathers thought, what they read and sources of poetry , art and music wove their lives together.

A must read for anybody with an interest in the Great War.

Thanks for a brilliant account of two very sad deaths which were, of course, only two among so very very many.

This day, 2017, a group of aged 50+ cyclists passed the memorial (of which I was one).

The sentiment we all felt is ever poignant, As we pinned a paper poppy to the step of the monument, the sense of sadness and feeling of gratitude was almost tangible.

The sacrifice and pain these families endured is unimaginable for us who enjoy freedom and relative affluence (by example, Buggins – two brothers lost in their prime).

We will not forget them.

Thanks for this beautifully written article. Im a great admirer of your blog, which i stumbled by chance and now follow closely everyday. You have a very sensitive way of telling these people story and I feel very close to each and every one of them, even though so much time has passed. Please keep up with your good work.

When the Antiques Roadshow was at Stanway, Lord Wemyss brought out that tryptich to be valued. Of course, it wasn’t — Fiona spoke with him about it. It was very moving.

Thanks for so nice and deep recollection.

Honour to their merit.

We ore them a lot.