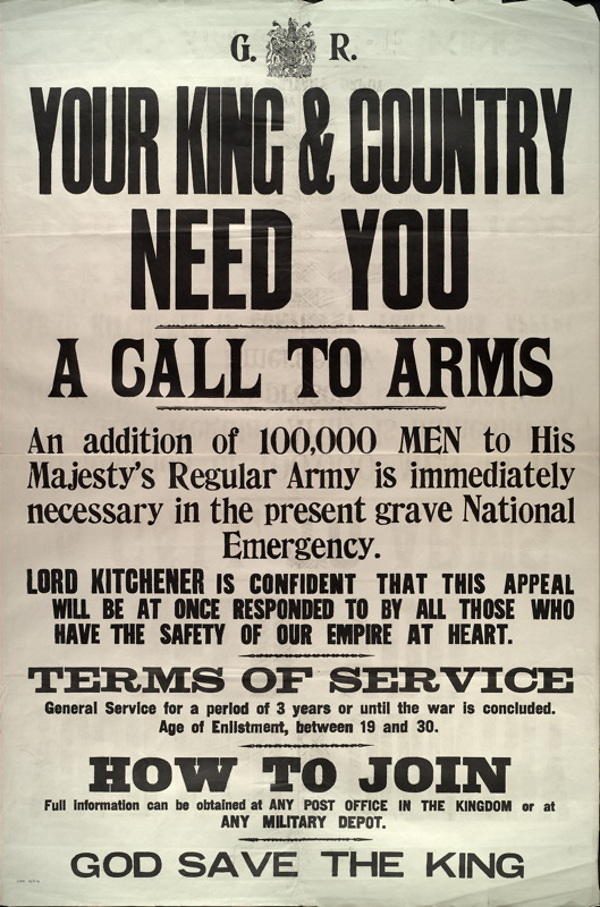

Kitchener’s poster declared, “Your King and Country need you”, but it was only once the Amiens Dispatch was published on 30 August that the British public realised just how much their King and country needed them.

was only once the Amiens Dispatch was published on 30 August that the British public realised just how much their King and country needed them.

Early on the morning of Monday 24 August, the day after the British defeat at Mons, Lord Kitchener brought Winston Churchill a telegram from General French: Namur had fallen, a general retreat had been ordered and in French’s opinion “immediate attention should be directed to the defence of Le Havre”. Both Kitchener and Churchill, the one Secretary of State for War and the other First Lord of the Admiralty, were appalled. The Allies were supposed to be halting the German advance at the French border; Le Havre was 210 miles away on the French coast. It looked as though a disaster was unfolding.

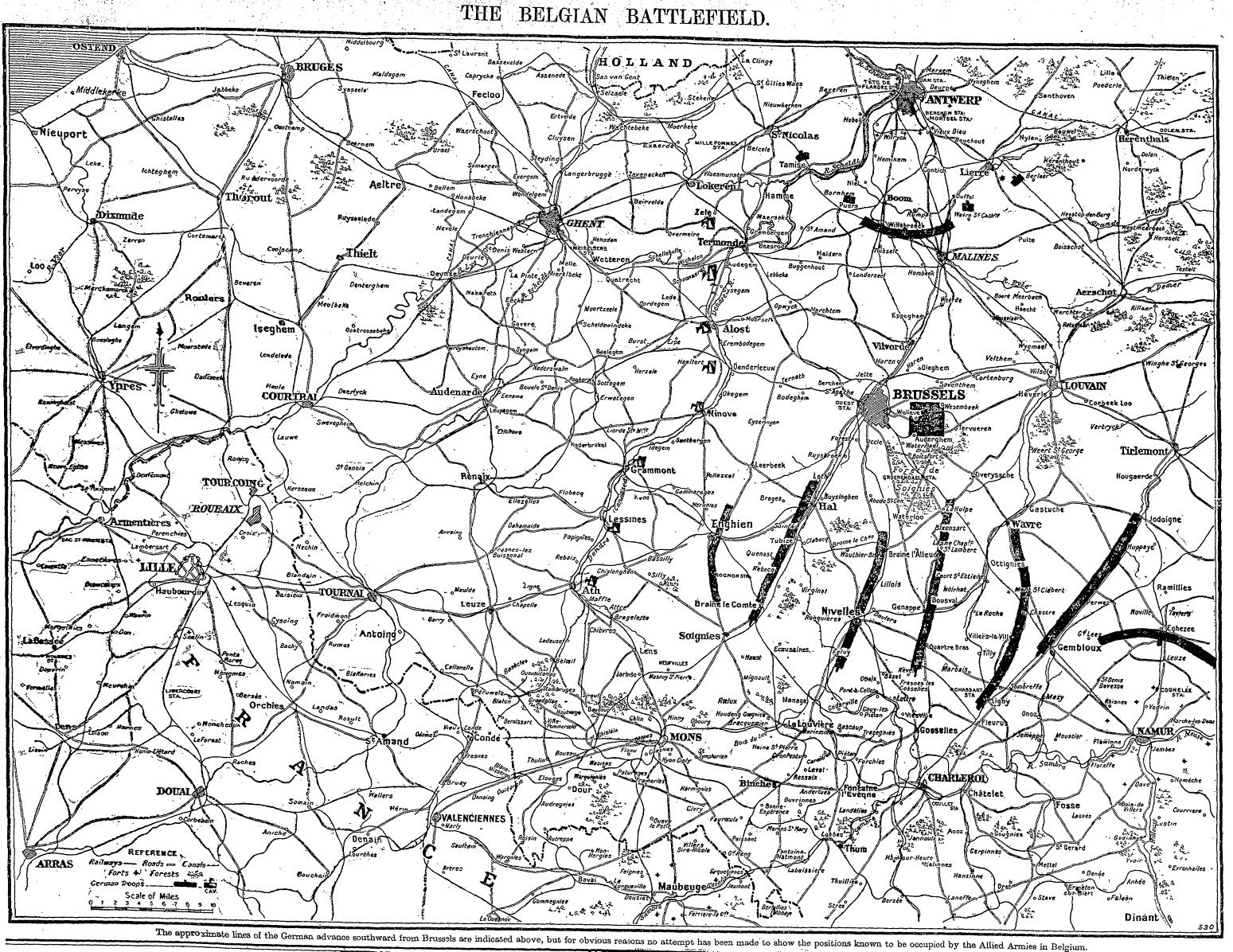

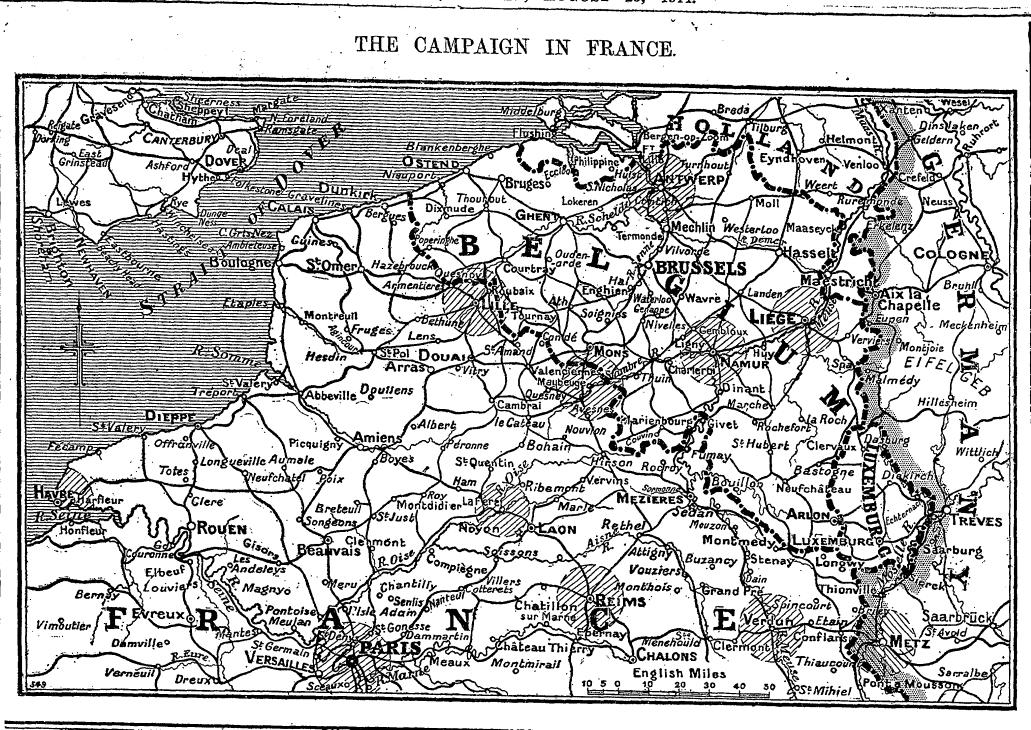

There was obviously no indication of this in that morning’s papers. A map in The Times showed ‘The Belgian Battlefield’ with the German Army as seven black arrows advancing towards the French border, but with Mons and Namur still behind the Allied lines. Tuesday’s paper carried the news that Namur had fallen but there was no sign of this on the map. Wednesday’s map, still described as ‘The Belgian Battlefield’, showed the Germans as having passed Namur but not Mons, despite the fact that Mons had fallen three days earlier. However, by Friday the map was now said to illustrate, ‘The Campaign in France’. It would have been obvious to even the most casual reader that all was not well.

The Times was not in the business of giving away information that might be of use to the enemy so of course it was not going to mark British positions on the map with any accuracy. The paper says as much at the bottom of each map, “for obvious reasons no attempt has been made to show the positions known to be occupied by the Allied Armies …”. But this wasn’t the only reason for not marking British positions with any accuracy. Wednesday’s paper hinted at the situation. Under the headline ‘British Gallantry’, the paper reported,

The Allies have fallen back, but their resistance has cost Germany very dear. The battle has begun; yet its first days rank it, according to past standards, as one of the greatest in its history.

This was followed by the warning,

Their losses have been considerable. They are estimated by the Field Marshal in command at over 2,000. No details have yet been received.

The next day, Thursday the 27th, there were grumblings in the press about the lack of information,

Though we know that the British Army acquitted itself with distinction at Mons, we still know very little more. Even the casualty lists are not yet made public.

Friday’s report, referring briefly to the Battle of Le Cateau, can only have increased the anxiety:

Our Army was heavily engaged yesterday in co-operation with the French against superior numbers, and once more it splendidly sustained its fighting reputation.

And Saturday’s even more:

Our soldiers have fought as men of the British race have ever fought, but it would serve no useful purpose now to hide the heaviness of the price of their bravery.

The British public knew little but feared much. There may not have been any official reports of casualties but this hadn’t stopped the press from finding out what they could. A report from Rouen on Friday 28th described the arrival of the wounded:

These were not the worst of the wounded, for the worst cases are still up country. Some had only bad feet, broken by heavy marching; others had bullet or shrapnel wounds in feet, or hands or head; a small percentage of the 500 had the stomach wounds which every seasoned soldier dreads; only one went through the pains of death upon the station.

The authorities were not keen for reporters to witness these scenes so that an article in Saturday’s paper under the headline ‘Wounded at Southampton’ could only report:

Special trains were in readiness at the quayside, and the men, it is believed, were hurried away to Netley. The public were excluded from the docks and the greatest secrecy was maintained.

A week after the battle had begun in France there was a battle raging in Whitehall. How much should the public be told? There were those who argued that the truth would be bad for morale and those who thought that by suppressing it the Government was “cutting off their best recruiting agent”. Not only this but, “The time is past when a great and free and enlightened democracy can go to war in the dark”.

Was this the reason why when a dispatch arrived from Amiens by special courier on the evening of Saturday the 29th The Times decided to see if they could publish it? As required, they sent it to the Press Bureau for censoring, having crossed out the most alarmist passages themselves. As the hours ticked by and they heard nothing they assumed that the whole article must have been censored. However, soon after 11 pm a courier brought it back with many of the crossed-out passages reinstated and fresh sentences added for extra emphasis. What’s more, the whole edited report had been signed off by no less a person than the head of the Press Bureau, FE Smith.

The Times, which had been preparing a special Sunday edition of the paper, went ahead and published. Breaking with all tradition it put a news story onto its front page. Under the headline – Fiercest Fight in History: Heavy Losses of British Troops – the paper delivered the latest war news, and then printed the Amiens’ dispatch under the headline – Broken British Regiments. It told “a bitter tale” of a “retreating and broken army … battered with marching” and “grievously injured regiments” with nearly all their officers lost.

It caused an uproar: The Times was accused of irresponsible sensationalism and by 3.40 on Sunday afternoon the War Office had issued through the Press Bureau a more upbeat version of events, together with a warning that in future such dispatches were to be treated with “extreme caution”. But as the Editor pointed out to his readers, it was the head of the Press Bureau who had encouraged them to publish it.

The dispatch may well have caused an uproar but the cat was now out of the bag. By the following Monday, 7 September, three casualty lists had been published detailing the loss of 15,080 men killed, missing and wounded. An accompanying note from the Press Bureau, presumably meant to encourage the public, reminded them that “the ‘missing’ include unwounded prisoners and stragglers as well as killed and wounded”. The public may not have been encouraged but if FE Smith and The Times had hoped that the truth might encourage recruitment they were right:

The men of London and the Provinces have evidently realised since Sunday that the success of Great Britain and her Allies against Germany can only be ensured by large additions to the British forces in the field.No one doubted that as soon as this was really understood recruits would come forward in abundance. Monday saw more men joining the colours than any day since the war began, and yesterday easily eclipsed Monday’s record. [The Times Wednesday 2 September 1914]

‘Your King and Country need you’ took on a different meaning when the army was in retreat, France looked as though it might fall and the enemy would soon be at the gate – well at the Channel ports anyway. In the six days between 30 August and 5 September 174,901 men enlisted compared with 100,000 who had done so in the three weeks between the 4th and the 22nd of August*. One of these men was Corporal Donald Noding, killed on 10 September 1916 whose headstone inscription reads:

Joined His Majesty’s forces

August 31st 1914

Proceeded to France

January 1915

* British War Enthusiasm in 1914: a Reassessment Adrian Gregory. Evidence History and the Great War ed. Gail Braybon Berghahn Books 2003

History Today article on The Amiens Dispatch

No Comments